“Have you seen this?” a DSA comrade messaged me. “It’s a police badge!”

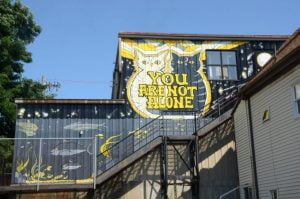

Linked were two news stories about a mural at 82 Gilman Street in Portland, Maine that depicted two cats—one white, one dark blue, overlooking a sea of fish, with the words “You Are Not Alone” prominently displayed. The articles said the piece was a collaboration with the Portland Police Department and part of a global mental health awareness campaign called “You are Not Alone.” Included in one article was a report on a new Community Policing substation that was moving into the Parkside neighborhood.

I had ridden by the mural on my bike several times and not given it much thought, but the news articles about its connection to the cops made me look closer at the central shape formed by the two cats, and outlined in gold. It looked exactly like a police shield to me, and those vigilant cats began to take on a new meaning in my mind. Posting to social media, and asking other friends and activists what they saw in the mural, the responses came back the same:

“You are not alone” mural by Kerrin Parkinson. Photo courtesy of Portland Phoenix.

“Oh, yeah. I saw it right away,” one said. “From a distance, you don’t see cats. All you see is this shield shape.”

Another texted, “It’s a badge. The cats are surveilling. That’s definitely a message.”

“Once you see it, you can’t unsee it,” a comrade said.

“Turn it black and white, and make it look old, and you’d be like ‘wow, the shit they used to do!’” another person said.

As my concerns grew over what appeared to be a copaganda campaign boosting Portland’s Community Policing Unit, so did my instinct to dig deeper. I began contacting the artist, the city, and the “You Are Not Alone” mural project to learn more.

Kerrin Parkinson, who painted the mural, was the first to get back to me. Kerrin is a thoughtful and kind person who was deeply saddened and upset that someone would accuse her of inserting subliminal pro-policing messages into her work. “The police department has zero influence on my work,” Parkinson said. “The only way the police were involved was they asked the building owner to consider a mural for the space which became frequently vandalized. The owner of the building and I were connected by the Police Department, and I proposed this design. The police had nothing to do with anything beyond connecting us.”

She said the two cats were based on her own pets, who have helped her get through tough times. The message she was trying to convey was about the importance of connecting to your support network, and she intended the controversial shape to be a fishbowl, not a police shield.

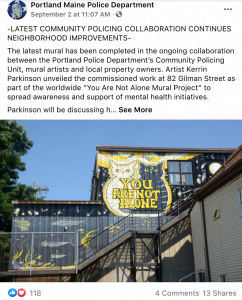

Parkinson also expressed frustration and disappointment over the newspaper articles, which crib heavily from from a September 2 press release issued by Police Department Communications Director David Singer. The press release lays claim to Parkinson’s work as “the latest mural in the ongoing collaboration between the Portland Police Department’s Community Policing Unit, mural artists and local property owners.” The release goes on to state that the mural “was commissioned in part to deter graffiti and vandalism,” and directed concerned property owners to contact the Portland Police Department if they want to partner on similar projects.

The Portland Press Herald quoted the release in its September 2 article in advance of the First Friday Art Walk, where Parkinson was scheduled to speak about her work. The Portland Phoenix picked up the thread four days later in an article on the creation of a Community Policing Substation in the same neighborhood. Though the mural is on a building a half-mile away from the new police station, they used a photo of the mural for the story, further connecting Parkinson’s artwork to the cops.

“I did not even know about this neighborhood policing effort,” Parkinson responded. “How can I collaborate with something I know nothing about? The writers never even interviewed me. No one reached out to me at all re[garding] either of these articles.”

“You are not alone,” courtesy of Portland Press Herald.

Richard Bianculli, Neighborhood Prosecutor for the Portland Police Department and the coordinator of the Community Policing Unit’s anti-graffiti program responded in an email, “Community Policing (me) connected the property owner with the artist after the property owner asked about a way to deter further vandalism. We had no input on the design whatsoever. We are merely trying to tell the public that you can deter graffiti vandalism with public art. That is why we did the press release about the mural,” Bianculli wrote.

This raises the question of what constitutes public art.

Jessica Grondin, official spokesperson for the City of Portland, denied that the mural was commissioned with public dollars. “The City did not fund any part of the mural. All funding was completed by the property owner,” Grondin wrote in an email. In a follow-up interview with Bianculli, he clarified that he considers “public art” to be anything that is displayed in public, not necessarily funded with public dollars. He said the city did not pay for the mural, and expressed regret that the department’s press release characterized the relationship as a collaboration.

You are not alone, and the cops are still watching

You Are Not Alone, based in New York City, is a project of writer Samantha Schulz and mural artist Annica Lydenberg. Out of 200 works that have been submitted digitally by artists from over twenty-five countries since the launch in 2019, the project recognizes only 24 murals, according to its website. At least two of these were painted by co-creator Lydenberg and include branding for Lydenberg’s design business, Dirty Bandits. Schulz’s book, I Don’t Want to Be Crazy, a memoir written in verse about her own struggles with anxiety, is heavily marketed on the project’s website. You can also click a link to invite her to speak about it.

Local artist Parkinson says she painted the Parkside mural for submission to the You Are Not Alone project but has not yet submitted the work for consideration because of difficulties photographing it. She chose a color palette that would conform to the project’s guidelines. Some have remarked the palette is similar to the Blue Lives Matter, a counter-movement to Black Lives Matter that seeks to justify police—and police violence—as the only thing standing between civilization and chaos.

Speaking on behalf of the project, Schulz denied any association with Blue Lives Matter, and said they also don’t believe the Parkside mural is associated with Blue Lives Matter. “If you had looked at our project, you would see the color palette is not police department colors, but rather the color palette that unifies all artwork created with our project. We also do not see the police badge you see,” Schulz said.

Across the United States, the risk of being killed during an encounter by law enforcement is 16 times higher for people with untreated serious mental illness than for other civilians, according to a 2015 report. Exposure to police violence negatively impacts people who already suffer from mental health issues, and can also be the cause of these issues. Neither Schulz nor Lydenberg claim any training or credentials in the identification or treatment of mental health disorders. They also don’t seem to see any problem with artists partnering with cops to prevent crime. “Many building owners decide to allow murals to be painted on their buildings to help diminish illegal graffiti. This is meant to help beautify a neighborhood and bring arts to the community,” Schultz said.

The Problem with Community Policing

Taken at face value, Community Policing is a law enforcement program in which officers work with residents in preventing crime. Critics of the program say it enlists only certain members of a community, usually gentrifiers, in an effort to build grassroots support for police under the gloss of beautification, and does not address problematic police practices and behaviors. They point to the heightened police surveillance that anti-graffiti programs create—not just surveillance of criminals, but also of artists, activists, and community residents who are drafted into working with the police directly or through association with others.

Portland Maine Police Department Facebook page

“Community policing is how police wield power within and attempt to organize neighborhoods,” said Brendan McQuade, assistant professor of criminology at the University of Southern Maine. In theory, he says community policing units work with neighborhoods to proactively identify “disorder,” a term which almost always is a euphemism for non-compliance with racial, gender, and class norms of behavior. In practice, cops enlist self-selecting local law-and-order lobbies to amplify police programs and report information to police.

“Intelligence gathering is the other side of the community policing coin. Every ‘relationship’ police build with residents can be mined for information or turned into a source of leverage,” McQuade explained.

Portland Community Policing spokesperson Bianculli said he maintains a list of artist names and contact information, as well as murals they have been involved in. He said Parkinson has worked on projects at 9 Somerset Street and 50 Monument Square in Portland and is known to have included the acronym ACAB in a mural. Bianculli did not specify which mural and Parkinson did not respond to a request for comment on Bianculli’s statement. Bianculli denied seeing a police shield, or any pro-police messaging in Parkinson’s mural adding, “Anyone who thinks that is cuckoo crazy-clocks, and I can’t help them,” Bianculli said.

This is not the first time local artists have balked at Portland Police Department communications that seek to link them with Community Policing. Last month, Gigi Gabor, a local a Black trans drag performer, and several other artists, pulled out of hosting the “One Maine One Heart” barbecue and concert for the homeless on Sunday August 29th in Congress Square Park, after the Police department issued an August 27th press release with an attached flyer depicting Police Commissioner Mike Sauschuck and Police Chiefs Frank Clark (Portland) and Jack Clements (Saco) as headliners at the event. Gabor, who uses they/them pronouns, said they were never made aware that police were involved in the event at all, let alone featured presenters, and only learned of the cops’ collaboration one day prior to the event when activists forwarded the flyer from the press release.

“The event was pitched as a way to unite the queer, Black, immigrant, and homeless communities–communities that are often siloed in our work. I was never told that the police were behind it. The police have done nothing to earn our trust and have caused emotional harm to the community with an event to feed the homeless, while destroying their belongings a few blocks away,” Gabor said, referring to the clearing of homeless encampments in Portland and the trashing of personal possessions, some of which have been caught on film and posted to social media. Maine People’s Housing Coalition activists also expressed concerns that the event would be used to surveille the homeless.

Cops and art don’t mix

Parkinson painted the mural in Parkside to bring awareness to mental health struggles and said she “would never intentionally inflict harm on anyone struggling. In fact, my mission is the exact opposite, to lift people up,” Parkinson said. Gabor thought they were participating in an event to heal the community of its divisions, not break bread with cops. “It can’t believe I almost accidentally hosted a cop event,” they said.

It’s not like the police are filling a void. Portland already has an office for the funding and creation of public art: Creative Portland. It is a partnership between a local non-profit and the City of Portland. It’s primary purpose, according to its bylaws, is to act as the official Local Arts Agency for the City of Portland.

“Let Equality Shine,” by Kerrin Parkinson, Candice Gosta and Sidney Sanchez, with detail by Candice Gosta, is painted on a building at Portland’s Monument Square. Courtesy Maine Public.

Executive Director of Creative Portland Dinah Minot says she was not made aware of the mural projects being arranged by Community Policing. She did state that Creative Portland can provide the kind of oversight and support projects like this really need. “We have the ability to vet artists, make sure they are fairly compensated, provide the right materials for a durable installation, and set a high bar for excellence.” She says she would encourage artists and organizations interested in public murals to let them in on the ground floor of a project. Creative Portland has to raise their own funds to complete projects and has only two full time employees, but Minot believes in the value of art to the city, not just as an economic engine of the city, but also as a way to promote community bonds and healing. Asked about how the #DefundPolice movement might free up funding for such programs, she said, “There’s a lot of work to do to convince people—the city and the taxpayers.”

Art that is displayed in public reflects not only the artist’s own intentions, but also the social conditions surrounding it. It speaks to a specific time and place, as well as to how we see ourselves in that space. Elected officials, homeless individuals, housing justice advocates, police and prison abolitionists, the immigrant community, the Black Lives Matter and Black Power movements, incarcerated youth, families and friends of those injured and killed by police, and the indidgenous people living on the land called “Portland” by its colonial occupiers, as well as many other allied voices, have been crying out for real changes to the city’s law enforcement approach to poverty, homelessness, substance abuse, and mental illness. The Police have responded by creating a Communications Director position to up their propaganda game, while continuing to back harmful community policing programs and performative police oversight in order to shield themselves. Perhaps even more concerning is the way the local press has responded: by reprinting Police Department press releases verbatim without bothering to ask questions. Viewed from that angle, maybe the mural in Parkside, with its cats in a fishbowl, is speaking loud and clear.