I watched Rustin on Netflix a couple nights ago. I highly recommend it—along with Spike Lee’s Malcolm X and PBS’s Eyes on the Prize—if you want a crash course in the Civil Rights Movement. It got me thinking about how socialists develop strategy (long term methods and goals) and tactics (individual or short term actions, campaigns, and mobilizations).

Back then, the Civil Rights Movement had run into a roadblock on the way towards desegregating the South. President John F. Kennedy owed his election to the Black vote (and labor), but showed little urgency to repay his debt. Alabama Gov. George Wallace stepped into the vacuum in early 1963, declaring “segregation today, segregation tomorrow, segregation forever.” Birmingham Police Commissioner Bull Connor made good on the governor’s threats, turning fire hoses and police dogs on nonviolent civil rights protesters in Birmingham on May 2. Within a few weeks, the backlash against Connor forced Kennedy’s hand and he delivered a primetime Civil Rights Address promising federal legislation.

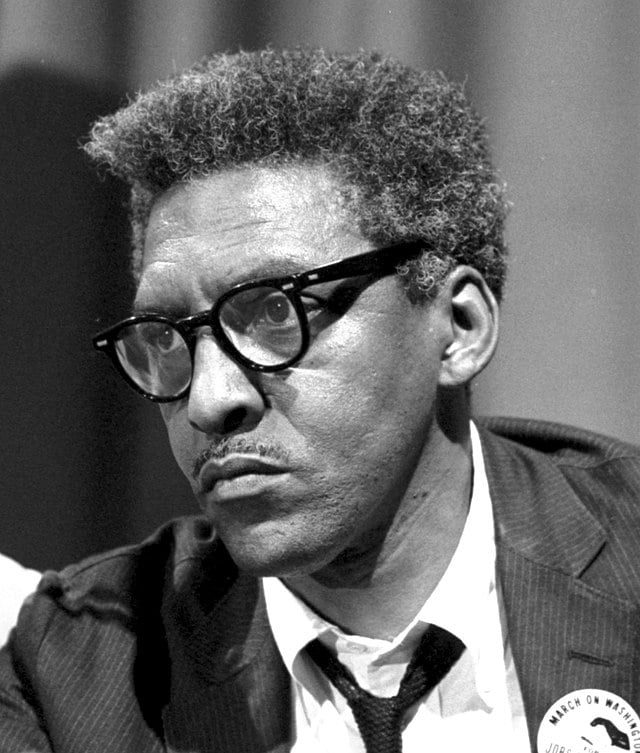

Enter civil rights strategist and tactician Bayard Rustin. While many Black leaders hoped Kennedy would finally act, Rustin refused to take the president at his word. He realized that the entire desegregation strategy might stall if a new tactic were not put into practice. Rather than backing off, he believed it was the time to push by calling for a national mass march and threatening to bring the capital to a halt. On August 28, 1963, 200,000 people joined the March on Washington and heard Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. deliver his I Have A Dream speech. Kennedy signed the Civil Rights Act within a year. It is fair to ask just how much credit Rustin’s intervention deserved; Malcolm X called it the “Farce on Washington” at the time. But there’s little doubt the march helped nationalize the movement. Studying this history is a must for activists committed to fighting for a better world and 1963 is rich in lessons for us today.

To have a plausible chance of winning, any movement must first determine its aims and a broad strategy for achieving them. Socialist aim to overturn the power of the uber rich and the militarized states that defend their interests. Our strategy relies on mass, democratic movements of the world’s poor, oppressed, and working-classes to build up our own political parties, unions, and social movements. This strategic idea is critical, but it cannot be put into practice all at once.

Tactics are how we put our strategy into action. The workers movement has developed a wide range of tactics over the decades dealing with unions, elections, mass protests, occupations, etc. One of the most important—and least appreciated today—is the united front. It’s the tactic that Bayard Rustin learned from communists and socialists in earlier years and which he put to such effective use in 1963. Fortunately, it’s not difficult to understand the basics.

First, choose concrete goals. These goals must create meaningful change (the the Civil Rights Act) even if they don’t challenge each and every aspect of the system. Ideally, winning such demands draws more people into the movement and leads them to want to fight for more.

Second, build unity between forces in labor, student, immigrant, feminist, LGTBQ, religious, progressive, non-profit, ecological, and socialist community groups, unions, organizations, and parties. These forces will not agree on everything, but they must be capable of mobilizing people to achieve our concrete goal.

Third, prepare for debate within the coalition. Sometimes, compromises within a coalition must be made to sustain the unity necessary to win; however, sometimes compromise leads to demoralization and betrayal. Knowing which is which is the art of political leadership.

Finally, if socialists and radicals can demonstrate that they bring valuable knowledge and mobilizing power to the table, we can convince more and more people that we cannot stop fighting until we overturn the 1%.

Rustin provides a master class in how to think about the first three of these points, even as it leaves the fourth—perhaps owing to its production company—to the imagination.

Sadly, even if we get all this right—as Rustin did in 1963—organizers can rarely rest on their laurels for long. Less than three weeks after the March on Washington, the Klan bombed the Birmingham Sixteenth Street Baptists Church, killing four African American girls.

Sixty years later, what does this mean for us in Maine?

Thanks to generations of organizers, we have a little breathing space. It is enough to think of our brothers in sisters and gerrymandered, right-to-work, Red States—never mind the people of Gaza or Afghanistan or Central America—to understand that our relative freedom of action comes with responsibility. People in Maine have demonstrated the ability to safeguard abortion rights, welcome thousands of New Mainers, raise our minimum wage, and grow our unions. We have built a self-defense ecosystem of local and statewide movements that have protected us from right-wing populism, if only just barely and only for the moment.

At the same time, we have not transformed the police or prisons, solved our housing crisis, made “life the way it should be” for LGTBQ youth, fully funded our public schools, or respected the sovereignty of the Abanaki peoples. We face public school budget cuts, sweeps against unhoused people, union-busting employers, an affordable housing crisis, inadequate public transportation, and a cost of living crunch. And we have to ask: How do these problems relate to building solidarity with Gaza? To challenging our governor’s veto of Wabanaki sovereignty? To confronting the MAGA threat?

Were he with us today, the real Bayard Rustin would look for a weakness in the wall of injustices we face in Maine. He would ask who can be convinced to discuss a plan to leverage our collective strengths against that weakness. Then he would get on the phone and get to work. It’s easier said than done, but studying and discussing Rustin just might make it that much more possible.