Global climate change is tightening its grip on Maine. It’s set to be 40 degrees or more and pouring rain on Wednesday, January 5, from Kittery to Farmington. I don’t know about you, but I find reaching for my umbrella after Christmas depressing. Worse, Year Three of COVID, the prospects for LePage Part II, and Don’t Look Up-level paralysis by liberal elites all strike me as more than a little daunting. Thankfully, Black Lives Matter has strengthened opposition to racism, “Striketober” points to the labor movement waking up, and opinion polls demonstrate young people are looking left. As a lifelong socialist (I first saw Bernie Sanders speak in 1988), I am heartened by the growth and tenacity of the Democratic Socialists of America and the movement more widely. But … we are still deep in the woods and the ticks are getting worse.

As a translator and activist, I’ve spent a lot of time trying to understand international political movements and I believe the U.S. Left has a lot to learn. But there’s only so much time in the day, so I’ve decided to focus closer to home by starting this column dedicated to Maine agriculture and food. I’ll be interviewing people who do the work and trying to shed more light on the organic revolution germinating in Maine and (I’ll keep the door open to) beyond. As a high school teacher, I’m looking forward to highlighting statewide efforts to introduce students to farming and food production and build stronger links between local food and public school cafeterias. At the same time, as a new farmer, I’ll do my best to explain the practicalities that come with starting up a small farm.

It turns out that Maine is an ideal place to learn the ins and outs of organic farming. From Wabanaki practices here in Dawland to Scott and Helen Nearing’s search for the “good life” to Eliot Coleman’s ingenious inventions to the Common Ground Fair and Liberation Farms, the land we now call Maine has nurtured countless generations of farming communities. Dirigo, Maine’s motto, means “I lead.” It’s a big boast for a small state, but there’s no exaggerating Maine farmers’ role in challenging the American Industrial Food Complex. There’s no better evidence for the claim than The Organic Farming Revolution: Past, Present, Future, published by the Maine Organic Farmers and Gardeners Association (MOFGA) to mark its 50th anniversary.

As Revolution makes clear, Black and Indigenous farmers—along with small farmers of all ethnicities across the globe—have long understood the techniques and relationships that make up many of the core components of our current conception of organic farming. Those understandings did not simply fade away, they were very nearly erased by genocide all across the country and right here in Maine. However, those methods were preserved by Wabanaki peoples against terrible odds and later rediscovered and reworked by generations of organic farmers. At the same time, independent streams of organic agricultural research and practice arose in Europe and the Americas and elsewhere. Thus, while growing locally, Maine farmers rely on truly international knowhow.

Of course, the “organic” label has gone corporate—see Amazon’s purchase of Whole Foods—leading some to scoff that small farms and democratic agriculture are little more than rural nostalgia or elitist dining fads. And even when food is grown locally, the people producing that food very often face hyper exploitation. Yet, small and medium farmers have a critical role to play in confronting what Italian socialist Antonio Gramsci characterized as an organic crisis facing humanity and the planet.

Expanding that role beyond the already impressive networks of farmers markets, Community Supported Agriculture (CSAs), appropriate technology, and indigenous knowledge into larger chunks of the public sphere (local schools, assisted living facilities and nursing homes, hospitals, etc.) in order to make good food accessible to the many and to rewrite land holding and petroleum-based food production is a huge task. But the climate crisis and COVID–and international capital’s abject failure to solve either–are driving a new wave of young and not so young people to care about agriculture and to get into farming themselves. They are not only concerned with growing, preparing, and eating healthy food, they have an eye towards building a social and political force to change the world.

Expanding that role beyond the already impressive networks of farmers markets, Community Supported Agriculture (CSAs), appropriate technology, and indigenous knowledge into larger chunks of the public sphere (local schools, assisted living facilities and nursing homes, hospitals, etc.) in order to make good food accessible to the many and to rewrite land holding and petroleum-based food production is a huge task. But the climate crisis and COVID–and international capital’s abject failure to solve either–are driving a new wave of young and not so young people to care about agriculture and to get into farming themselves. They are not only concerned with growing, preparing, and eating healthy food, they have an eye towards building a social and political force to change the world.

There are as many reasons for us to invest energy and solidarity in agriculture as there are varieties of Heirloom tomatoes. There’s no way to rein in the climate crisis without redesigning how we get our food. Technically, depending on how you count it, global agriculture accounts for approximately 25% of annual greenhouse gas emissions. Socially, growing new food habits programmed by Coke and Cargill will have to be fought out refrigerator by refrigerator and elementary school by elementary school. Politically, Trumpism has made deep inroads into rural and semi-rural America, especially former mill towns and other economically depressed areas where farmers are often core constituents.

And right here in Maine, the climate crisis and COVID are creating an influx of people seeking refuge. If we want to greet them with open arms, unions, living wages, affordable housing, and quality public schools, we’ll need to plan ahead. Otherwise, opportunists like LePage will fuel resentment at “people from away”–although not out of state capital–to drive their reactionary agenda.

Fortunately, at a moment when we need it most, there is a bit of good news. As Bill McKibben puts it, “Farms are on the increase—small farms, mostly growing food for their neighbors. They’re not yet a threat to the profits of the Cargills and the ADMs, but you can see the emerging structure of a new agriculture composed of CSAs and farmers’ markets, with fewer middlemen. Which is all for the good. Such farming uses less energy and produces better food; it’s easier on the land; it offers rural communities a way out of terminal decline. You could even imagine a farmscape that stands some chance of dealing with the flood, drought, and heat that will be our destiny in the globally warmed century to come.”

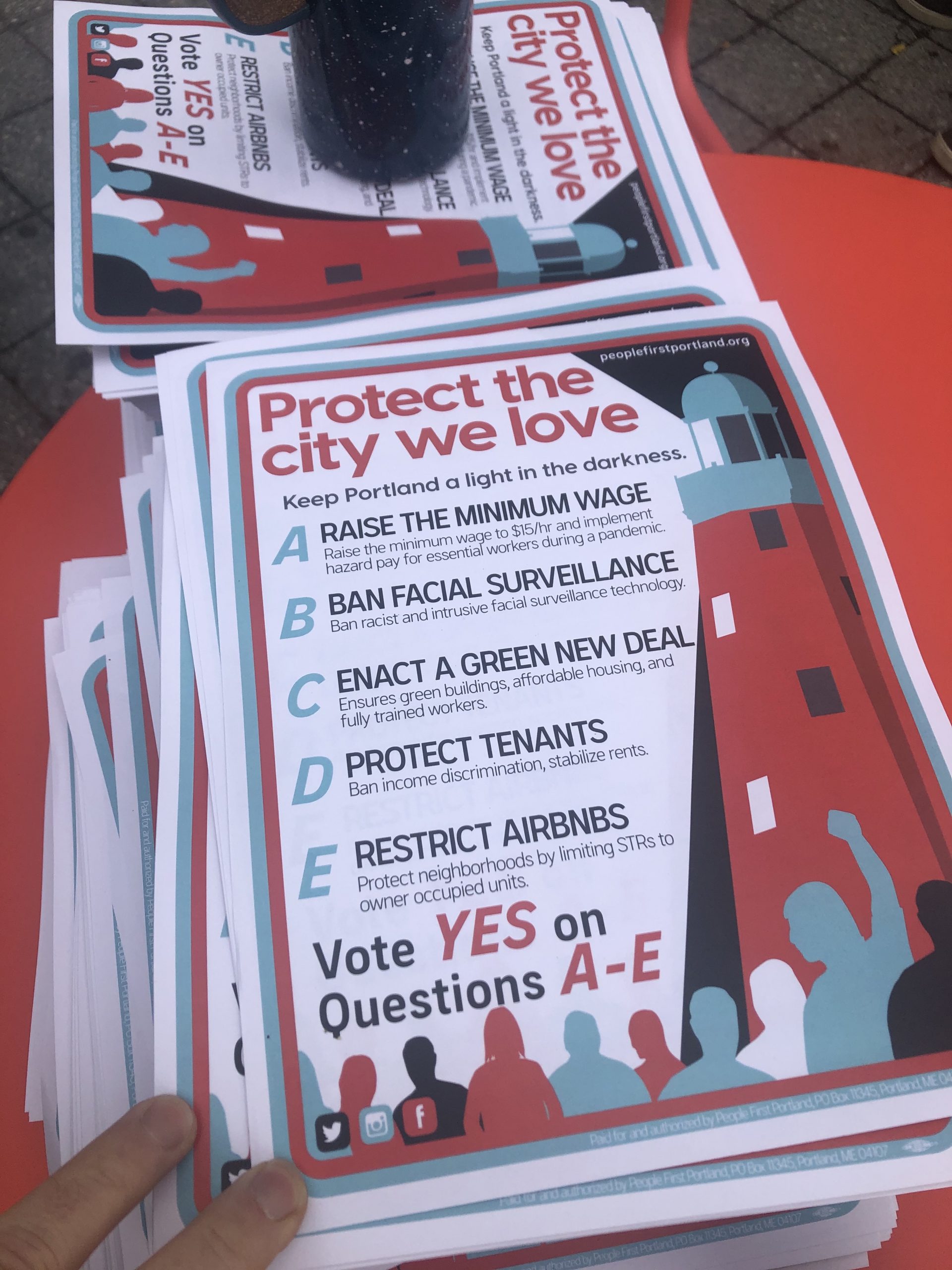

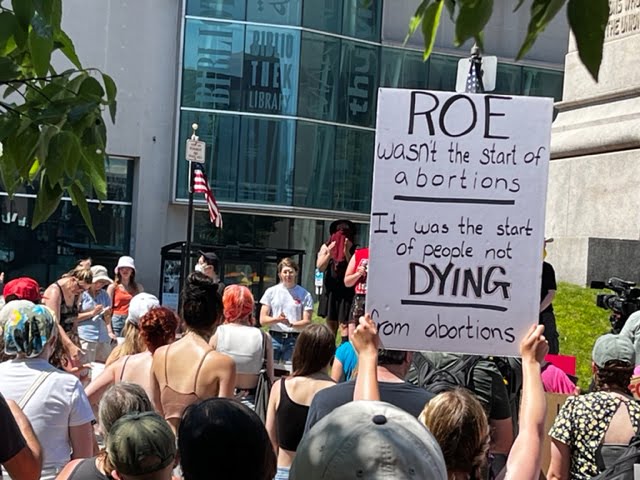

Unfortunately, we’re up against powerful foes in Big Ag and Big Oil. The Green New Deal promoted by Bernie Sanders, Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez and many others provides part of the framework we need, but after watching Joe Manchin chop away at Build Back Better, it’s clear there can be no progress without a fight. In order to win that fight, we need farmers to speak up for the people, and we need more people to become farmers.

It goes without saying that farming communities and organic agriculture cannot themselves be the solution, that is, reconstructing our food system is a necessary, but not sufficient, goal if we want to change our planet’s course. In the twenty-first century, there’s no use in going back to the land to flee from the ills of society at large; instead, many of us will have to find our way back to the land to help free society from those very ills.