Growing up on the coast and far away from any of the mill towns like Augusta, Waterville, Lewiston or Biddeford, the only thing I knew about French-Canadians was what I learned from my dad. He grew up with a lot of French Canadians and he said the stereotype was of the “dumb Frenchman.” He said they’d usually take shop classes in high school and went directly to work in the mills after graduation. They called them “frogs.”

What struck me most about these stories is that he seemed to be describing them as another race of people — an inferior race to many Yankee Mainers back in the day. He talked about going up to Quebec City after high school to party with his friends in the late 50s and how “those French Canadian girls really went wild for us white guys,” like he was telling a war story from Vietnam.

When LePage was elected, my dad said with some sympathy, “Finally they elected one of their own and he goes on to prove every single ugly stereotype about them.” I remember telling these stories to a couple of my Franco-American colleagues in the Legislature with some amusement because it seemed so ridiculous to me. But my friends reacted with visible anger. They weren’t that much younger than my dad’s generation and didn’t appreciate being reminded of the way Yankees viewed the French.

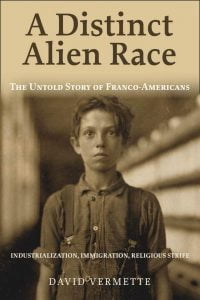

I’ve been reading this book “A Distinct Alien Race: The Untold Story of Franco-Americans” by David Vermette, which tells the story of the farmers and laborers who came down from Quebec to work in the textile mills of New England after the Civil War until 1930 when tighter immigration controls were put in place.

The early textile mills in New England got up and running after the War of 1812 as entrepreneurs–whom Vermette likens to Silicon Valley innovators–began taking ideas from England to establish a home-grown textile industry as the devastating wartime blockade prevented trade across the Atlantic. New England eventually became an industrial powerhouse, not just because it had the great rivers to power them, but also because the entrepreneurs enlisted talented machinists who developed the technical expertise to create a powerful and efficient industry here.

The fear of many locals was that these factories would create a mass working class like in England, which they associated with crowded, disease-ridden urban slums filled with factory wage slaves whom were treated little better than machinery. That’s why families like the Cabots, who owned the mill in Brunswick, and the founders of the Lowell textile mills envisioned a workforce of mostly young Yankee women who lived in dormitories with strict paternalistic rules meant to protect “feminine virtue.” It was expected that they wouldn’t become a permanent working class, but simply get married off and be replaced by more young women–and children, a lot of children were also sent to work in the mills. Many of these women were educated and the Lowell workers even had their own literary journal, the “Lowell Offering.”

Even Charles Dickens marveled at the treatment of American textile workers compared to the deplorable conditions of factory workers in England. He was impressed with the level of sophistication of the women and their literary interests as well as the accommodations in the dorms like grand pianos, which would have been a luxury in England. He described the Lowell textile women as “healthy in appearance, many of them remarkably so, and had the manners and deportment of young women: not of degraded brutes of burden.” He described the conditions of Lowell and England as “between the Good and Evil, the living light and the deepest shadow.”

Of course that was all mirage. No matter where you lived, working in one of these textile mills from sun to sun sucked big time. The first strike among Yankee women textile operatives occurred in New Hampshire in 1828, followed by strikes at Lowell in the 1830s. In 1841, nearly 500 female factory workers went on strike at Saco’s York Manufacturing Company over wages, housing, and paternalistic rules. They paraded up Main Street, chanting and singing: “We are not slaves!—We scorn the name! We ask not friend’s or foreman’s favor. We’re freeman’s daughters—and we claim the rights that woman’s father gave her!”

As my friend Charlie notes, some were shocked at their “seditious” behavior which was so unbecoming to the “feminine delicacy.”

That was one of the reasons why the factory bosses decided an immigrant workforce would be much easier to control. By the end of the Civil War, as the Irish and French-Canadians from Quebec began replacing the Yankee women, the Boston textile barons pretty much gave up on their utopian industrial experiment. As Vermette writes, “Gone were the literary journals and the visiting dignitaries; there to stay for a long tenure were overcrowded tenements and slums.” One Yankee former textile worker named Harriet Robinson later wrote in 1898 after the visiting the mills that about two thirds of the workforce consisted of “American-born children of foreign parentage.” She contrasted the “jubilant feeling” the young women of the looms once had to the “tired hopelessness” of the latter-day workers whom she describes as “underfed” with a “prematurely old look.” The only views were brick walls and the air was so hot and stale that she could hardly breathe. Housing in the neighborhoods around the mill was in a “dilapidated condition” with “houses going to decay, broken sidewalks and filthy streets.”

French clubs like this one have become de facto support groups for African immigrants in Lewiston, Maine. Susan Sharon/MPBN

For good Anglo Protestant Yankee women, the public would consider these conditions to be abhorrent and unacceptable, but since it was only Papist French peasants, the mill owners no longer needed to recognize the humanity of their workers. As one mill manager wrote during that time, “I regard my work people just as I regard my machinery. So long as they can do my work for what I choose to pay them, I keep them, getting out of them all I can…when my machines get old and useless, I reject them and get new, and these people are part of my machinery.”

Well, we know what happened next. After they all eventually unionized, globalization killed off the textile mills and later generations of French Canadians, Irish, Italians and other ethnic white workers simply assimilated and became “white” in the eyes of American society. Darker skin pigmentation was what was left to identify people who belonged to a lower caste and thus, according to our society, deserve to be treated as such. It’s why the newer immigrants from Africa are still going to have a much rougher time here than the white population no matter how hard they try to assimilate.

I remember a visiting friend from college remarked that he was surprised to see mostly white people working in restaurants and retail stores because where he was from it was mostly Black and Latino people doing these jobs. With our aging demographics and service sector employers desperate to fill these low wage jobs, I imagine that the demographic make up of these workers will rapidly change in the coming years. I think the lesson of textile mills is that we can easily justify treating other humans like property if we view them as inferior. This attitude isn’t just directed toward people of color as there are plenty of white workers who are viewed this way, but unfortunately that’s most often the image reactionary people think about when we debate policies to uplift the working poor.