Maine Youth Justice: No children in prison

Maine Youth Justice is a nonpartisan campaign fighting to end youth incarceration in Maine led by young people who have been incarcerated in Long Creek and directly impacted by the juvenile justice system. MYJ’s Abdul Ali and Al Cleveland spoke to Pine and Roses’ Sainte Harkins about their campaign to close Long Creek Youth Development Center, the end of youth incarceration, and the reinvestment of the $18.6 million dollars currently being spent to lock up Maine’s youth. The organization is advocating the passage of L.D. 1668 that, as State Representative Grayson Lookner and Abdul Ali wrote in the Portland Press Herald, would “turn Long Creek into a community center with supportive housing, instead of a place of trauma, harm and punishment. It’s time to create the future of youth justice by investing public dollars in a continuum of community-based care to replace incarceration for Maine’s young people.” This interview was edited for clarity and length.

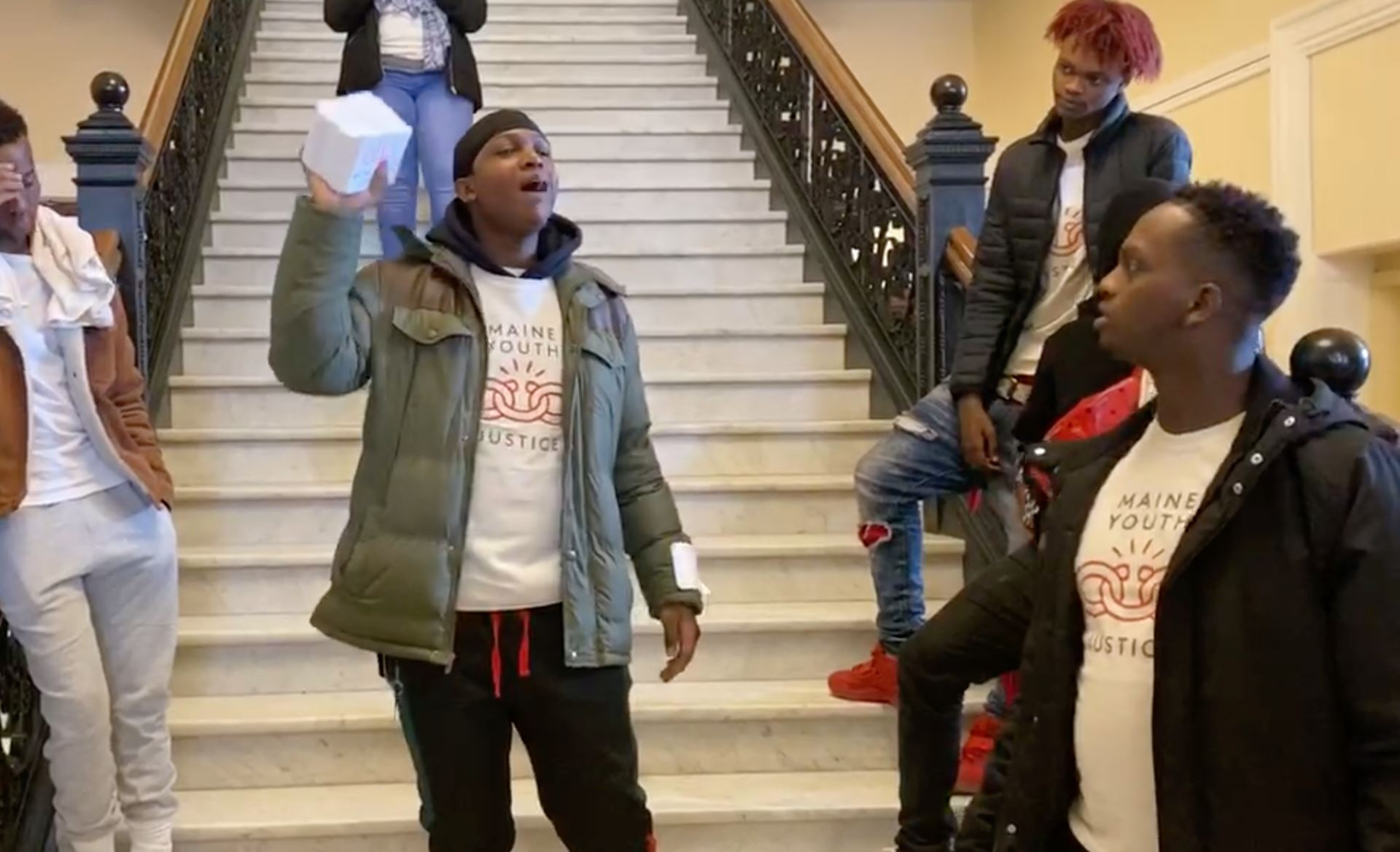

Image courtesy of Maine Youth Justice

Sainte Harkins: Hi everybody, this is Saint Harkins from Pine and Roses, our new socialist publication in Maine. Today we have two special guests: Abdul Ali and Al Cleveland from Maine Youth Justice, and we’re going to talk to them about their campaign to close Maine’s last youth prison, Long Creek detention center. Thank you for speaking with us today. Let’s talk about Maine Youth Justice’s goals and some of the core values that go into Maine Youth Justice.

Abdul Ali: Where did it start… Maine Justice actually started as a campaign two years ago, but prior to that, there was a sister organization that did work inside and outside of Long Creek with youth and that was called Maine Inside Out and they did “Theater of the Oppressed” and shared stories through theater as a tool and exercise for personal therapeutic work and also to tell stories to the communities and to hopefully change policy and what not. Following seven or eight years of doing that work, there was enough pressure — not pressure — but conversation within the communities, talking about what’s really going on inside the juvenile facility that’s harming and failing the youth. And that’s when Maine’s Youth Justice had an opportunity to really launch a campaign that’s actually going to push for the closure and reinvest the 18 million dollars that’s going through the building back to the communities that need it most.

Image courtesy of Maine Arts Journal

SH: As for the pending legislation, do we have any feelings? Are we feeling positive or negative about it, especially with it coming up so soon on Monday [in a hearing in the legislature].

Al Cleveland: Maine Youth Justice has been working with representative Grayson Lookner, who is a DSA member and socialist, to create the first piece of legislation that would create a plan to close Long Creek and reinvest 18 million back into the community. Not only that, but to turn the property that is being used to incarcerate twenty-seven young people into a community center with supportive housing. Maine Youth Justice organizers and young people who have spent time in Long Creek have had visions for that land being used to serve the needs of that community and not to cause more harm and violence inside the community. So we’re really excited to support L.D. 1668 and are really asking folks to show up to the hearing on Monday [May 14] and more importantly to reach out to members of the criminal justice committee and their state representatives and state senators and urge them to support L.D. 1668 as it is the pathway to close Long Creek by 2023, while giving young people with experience inside the system and people with experience with incarceration a central role in figuring out how we reinvest the operating budget of the facility, which is a crucial aspect of the campaign to close Long Creek — including the people who have experienced so much harm and abuse in the last few decades.

SH: I have a quote here from Maine Youth Justice, actually, saying that Black youth make up 23 percent of the youth at Long Creek, which is twelve times the Black representation in Maine’s youth population at large, so it’s a jarring statistic. In that same line, I think COVID has affected us all, but there is an invisibility about how it’s affecting people that are incarcerated. Would you want to speak at all to how people not only in Long Creek, but in other incarcerated situations, are dealing with the pandemic, dealing with getting vaccinated, and dealing with often unhygienic conditions?

AC: Young people currently who are incarcerated in Long Creek have been in what’s often compared to solitary confinement since the beginning of the pandemic. When a young person is detained and taken to Long Creek, since COVID began, they’re forced to spend two weeks in isolation. This means two weeks without any interactions with their peers, they’re displaced from their community, their family and their support system. This is traumatic for any adult, and there is an abundance of research to show why solitary confinement should be illegal. This is exacerbated when it happens to young people and folks whose brains are still being developed.

Young people who are leaving Long Creek are left with zero support about how to transition into a world with the pandemic. They are not supported with access to technology, housing, or healthcare, which we know are necessities when folks are battling COVID19 in their communities. In addition, we know that incarcerated people have been at a higher risk of catching COVID because they don’t have access to social distancing and other ways that folks can keep themselves safe. We know that there’s currently an outbreak of COVID19 with incarcerated women in Maine’s correctional center, and we know that since the beginning of the pandemic that over twelve Long Creek staffers have tested positive for COVID19.

On top of that, the vaccine for COVID has not been made readily available for folks who are currently incarcerated. Maine Youth Justice has been putting pressure on the Maine correctional system to make that vaccine available for people under 16, but that has still not been made an option for them. These are all huge questions that people are asking and we know that it proves that the Department of Corrections has failed to show that they’re a responsible agency to care for young people and adults. And if they don’t have the public health framework that they need to keep people safe, they shouldn’t be trusted with public dollars.

Image from Maine Youth Justice FB

SH: A good question related to that is how COVID has affected organizing. For instance, I think that with DSA and this publication we’ve seen a lot of growing support, but there’s also a lot of interesting barriers. So I’d love to hear some of the pros and cons about the organization and its growth during the pandemic.

AA: What I would say about the pandemic itself is it gave me a different perspective on how it slowed everyone down and brought people back to the ethical and moral parts of life, rather than chasing the world and its capitalistic system. A lot of people started to realize what’s important, in particular what youth need. There’s a high depression rate, the suicide rate is up.

We also see the Black Lives Matter protests that broke out not only nationally, but internationally. They sent a statement that there’s a lot of issues within our systems, criminal justice being one of the worst, that needs transformation. With that being said, [COVID] increased our platform where people started to contact us saying, “hey, we’re noticing a lot of these issues. Is there anything we can do?” That’s when we started to educate folks throughout the state, throughout the government, the city government and state government, on these issues. We’ve done tons of workshops, we’ve led peaceful protests, we’ve worked with colleges, universities, high schools, and right now I think what we’re seeing statewide is there’s such a push to reinvest the money back into the communities that need it most, because of the disadvantages of the 1990’s and early 2000’s, of how the communities have been split and underfunded in certain areas. Most of the [incarcerated] youth are not coming from suburban areas, because suburban areas have the resources they need for youth to thrive. So you see a lot of these issues happening more in the marginalized communities. And that’s not just a coincidence.

What COVID-19 did was it gave the opportunity for the Department of Corrections to decarcerate folks from the juvenile facility, so we know it’s possible. We don’t have to incarcerate these children now. There’s roughly twenty-six in the state who are incarcerated, so do we even need this incarceration system when it’s only harming youth, when we can, instead, rebuild that community so we can make everyone thrive?

SH: I was very close to the situation when Charles (Maze) Knowles sadly passed away, and that situation was tragic. I knew many people very close to him, and I met him on numerous occasions. He was part of the community. So when I think about the recent lawsuit against Long Creek, what kind of justice do you hope for Charles Knowles and his family now that we’re getting to this?

AC: I think the only people who can ask for justice for Maze’s death are his family and community. The campaign we are calling for demands accountability for all the people who have been wrongly incarcerated as young people at Long Creek and Maine Youth Center, the old youth prison, the Cottages, and the history of youth incarceration and incarceration in the state. We know that justice does not look like prisons or policing. We know that justice is something we have to build collectively, which is why we’re calling for the resources to do it.

We cannot be expected as a community to figure out alternatives to prisons and policing with $5,000 or $10,000 grants, we’ve already been developing them within our neighborhoods, practicing, experimenting restorative and transformative justice and that needs to be funded. People need access to housing and healthcare in order to organize, and that’s why we’re calling for resources to be divested from Long Creek. As a campaign, we know that families of folks who have died because of Long Creek are going to fight in every way they can to get justice and accountability for their loved ones. We encourage them and support them. The young people of Maine Youth Justice are calling for the closure of the facility, and rebuilding it into something that serves young people and no longer incarcerates them.

Maze Knowles

AA: To add to that, Maze was a person who was dealing with a lot of personal mental health issues that Long Creek only intensified. It made it worse. It’s very sad, just imagine that someone could go into a system that could take them and they couldn’t get out. The only way they could get out is by getting out of this life. That right there makes a point about what people will do just to get out of a system like that. There are so many stories, there are people I know, who I grew up with, who are buried, or going to constant funerals. So the reality is, what are the outcomes of youth incarceration. We have a 44 percent recidivism rate. We have people who are dying. We have drug addiction. We have bad relationships, traumas that will never be cured. Long Creek divestment is just a start. 18 million dollars is not enough for this state’s youth to thrive. We want a full diversion of how our communities are affected and what they need to be built. And [getting justice for] Maze is just a start, a huge, huge target where people can focus and start out.

SH: Yeah. It’s a stark example of something that happens all the time. When I was personally put in, incarcerated and then medicalized, I was often put in the men’s ward despite being a trans woman. And those kinds of things can really harm the mental health of trans youth that are put in these places, among obviously the many other harms to their mental health. I would also love to discuss the fight to ban police surveillance as well as the discussion of police and prison abolition versus reform in this struggle.

AC: At Maine Youth Justice, we are specifically a youth-led abolitionist campaign because that prioritizes youth organizers who have the experience of youth incarceration in the state. We specifically believe that there is no way to reform youth incarceration, the juvenile justice system, the youth incarceration system. We need to completely abolish it and build something else. We believe as youth organizers that closing a youth prison, showing our community that young people have no place in prisons, is a pathway to make abolition common sense, as we’ve learned from the No Cop Academy campaign in Chicago in 2016. Their goal was to make abolition common sense. Similarly, the work to close Long Creek, its goal is to make abolition common sense. We don’t need a place to lock up young people. We don’t need a place to lock up women. We don’t need a place to lock up men. We need places where people can get resources, people have access to healing, and people have access to the basic needs, and things that they, to give them access to creativity, to not just have their basic needs met, but to be able to thrive. We know that’s possible in a state that spends millions of dollars on policing and incarceration, and we know that Long Creek is the first place to start, by getting away from the system of punishment and moving into a system of care and solidarity and love.

AA: There’s data and resources to back it up that surveillance doesn’t make people safe, right. Surveillance actually causes more harm. If you read End of Policing by Alex Vitale, it explains how people that are surveilled consistently and constantly actually have more anxiety. It causes more issues when trying to live day to day because people don’t have the personal freedom they need to have to build their own emotional intelligence, mental intelligence, financial intelligence, and to thrive, right. So if you really look at surveillance, surveillance is just another key way of confinement in the and carceral system. What people need is not only the freedom, but to have the tools to build themselves so they can have a thriving future, if that makes sense.

When it comes to policing and whatnot, we see what happened between the 1980s and 1990s [and today]. [The numbers] increased to 2.3 million people that are incarcerated, 5 million people that are on probation, over 70 million people and growing that have criminal records. It’s 25 percent of this country, and we see the huge damage that it’s done. So, policing is not the answer. The answer is getting the support that people need. It could be therapy, it could be regular just hospital visits, it could be education. There are so many different things that we can do to thrive as a country. And I think that understanding that we constantly throw police at every situation — it makes police officers uncomfortable, we already hear that from them — it’s just not the answer. So we know we have to do something new.

SH: Well, thank you so much for both of your time. Everything you’ve said has been so salient and powerful. Is there anything you’d like to quickly say to talk about how people can support Maine Youth Justice?

AC: Thanks everyone so much. Please go to maineyouthjustice.org and sign up to get on our email list to get updates about the campaign. You can follow Maine Youth Justice on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram for updates about the work to pass L.D. 1668. And we’re asking all of our comrades to contact members of the Criminal Justice Committee to make sure they’re going to be voting to support L.D. 1668 at the work session.

AA: I would just say like, you know, the time is now. We have one youth prison left. It’s happening all over the country and, you know, if you just think about it: children in prisons. How does that sound? It doesn’t even sound good on the tongue, so I think that we really need to start pushing the action and really finding the solutions that we need. We have the research there, you can look online, you can ask us. But we can’t make it happen without you guys, so we appreciate you.