This is Part Three of an ongoing series focused on the increasing phenomena of burnout in the work place. Please read to the end to find out how you can connect with the authors to contribute your story.

“Well, Chris, we appreciate your two weeks’ notice, but we’re going to ask you to leave now.” Dustin, who was at the bottom of a chain of managers who were all my boss, seemed uncomfortably apologetic, like he had been given the task of asking a family member to leave the Thanksgiving table. “We’ll pay you for the next two weeks. We just think it would be better if you weren’t here.” His face had a crestfallen look that struck me as funny, and he walked a step behind me as we went to the locker room so he could watch me gather my belongings and, I guess, make sure I wasn’t stealing anything. He fidgeted as I emptied out the locker, clicking his ballpoint pen open and closed.

“What did they think you were going to do, take a shit in a filing cabinet?” my union rep said when I called him on my way home.

It’s hard to describe the relief I felt, the exhilaration of being a free man, out on the street on a late morning of a weekday. Working in a place where you’re behind a barbed wire fence, there’s a certain kind of low-level awareness that you can’t leave, that gets stored as a tension in the body. As I walked home, my arms and legs felt light. I looked around me with a smile on my face, and I felt like I did when I was a teenager playing hooky from high school.

I had been working for the Portland Water District for the last five years, as a maintenance electrician in their wastewater treatment plants. It seemed like the easiest job in the world at first. After working on construction sites for years, with somebody always telling me to hurry up, and the threat of a looming layoff just around the corner, work at the Water District was more human-paced. But there’s always a trade-off. For one thing, just about every piece of equipment I worked on–pumps, motors, conveyors–had all been covered in human shit and, in some cases, still were. It’s not easy to convince yourself to climb down a ladder, into a tank, and onto a platform that’s literally floating on top of raw sewage. Tyvek suits, rubber boots, and latex gloves only go so far. Plus, decades of mismanagement and underfunding had created an environment where everything was more or less falling apart.

And it wasn’t just the equipment that was falling apart. The social compact, the truce in the class war that defined the mid to late 20th century, was in tatters. The Water District, from its beginnings in the early 20th century, employed mostly people who worked with tools and with their hands, operating machines. There were a small number of managers to plan the work. But from the 1990s until now, the managerial class grew and grew, and they continuously shrunk the number of actual workers, so that now there is about an equal number of managers and workers. It seems impossible that their meetings and Powerpoint presentations can be a productive use of ratepayers’ money, but somehow it has become a self-perpetuating system.

Colleges and universities keep churning out people who think their place is not to make things or fix things, but to plan things. Not only that, but the culture at large has taught them that they are more intelligent and capable and responsible than those of us who work with the tools. And they have been given the task of disciplining the work life of the people who actually fix broken water mains, install water meters, operate wastewater treatment plants–the people who actually do the work, and their disdain and disrespect for us workers is deep and plain to see.

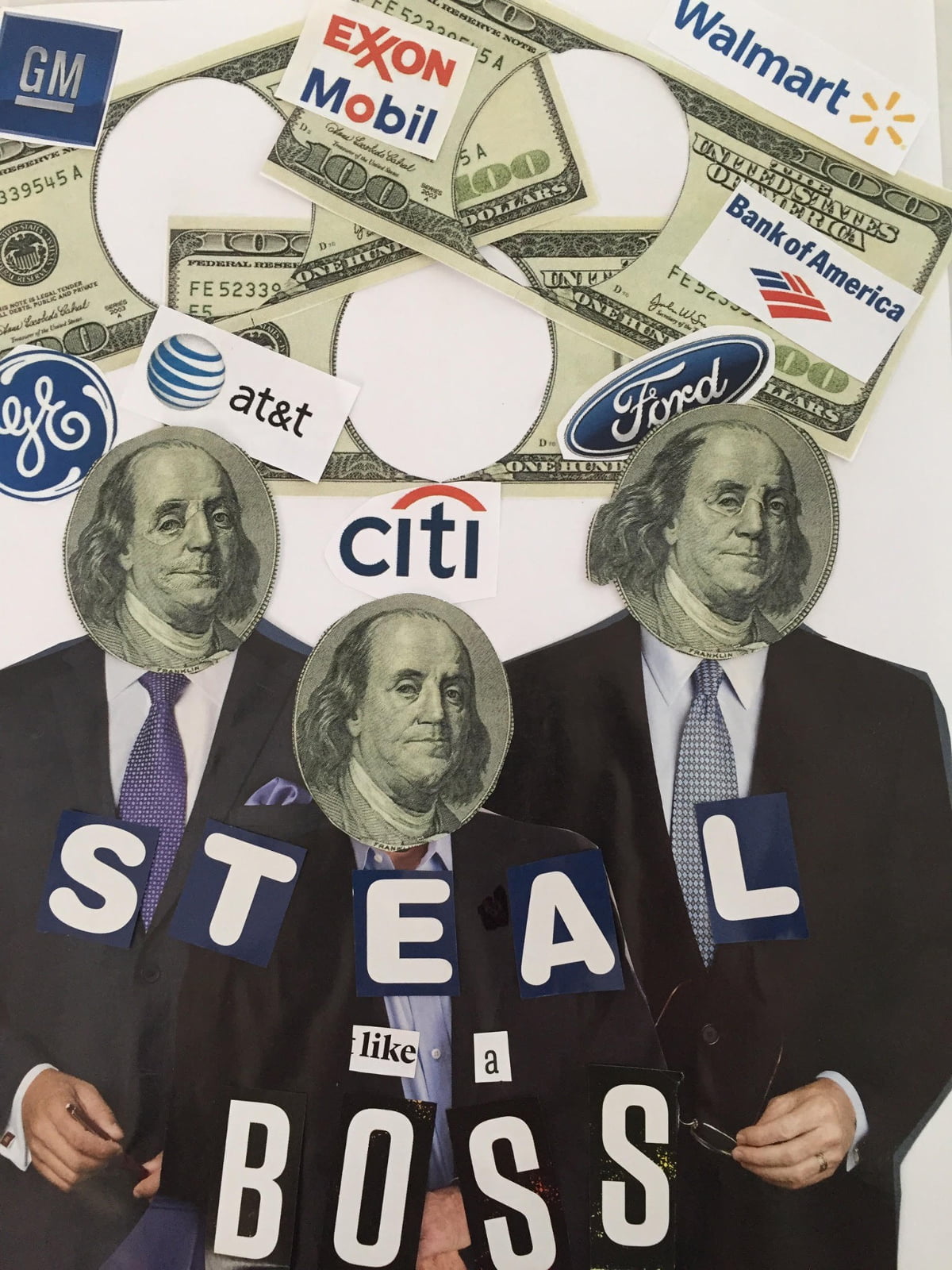

When I started working there, I volunteered early on, right after my probation was over, to be a union steward. I work with my hands, I work with the tools, but I’ve been to college. I know how to talk like office workers do, so I figured I could help translate between these two mutually suspicious and antagonistic groups of people. Yes, I was on the side of the workers completely, but I didn’t think the management people were necessarily as fucked up as my co-workers told me they were. After all, I thought, this isn’t Exxon Mobil, or WalMart. These people aren’t trying to make a profit, they’re just trying to provide drinking water and wastewater treatment. But immediately when I started going into discipline meetings, filing grievances, negotiating the contract, the management recoiled in horror at a union steward who wasn’t deferential, but expected them to treat me and my co-workers with respect. My relationship with them went from bad to worse, as the older guys I worked with all grinned and said, “We told you, Chris. They’ll never listen.”

Conditions for public-sector union workers are still way better than they are for private sector workers, let alone non-union workplaces, but any worker who has worked for a public utility for the last thirty years will tell you that conditions have worsened for workers that whole time. Maybe the most frustrating aspect of it is the constant surveillance, the assumption that workers are like children that need to be watched and punished all the time.

A couple months before I quit, me and another electrician were driving the company truck back to Portland after fixing something at the Cape Elizabeth treatment plant. We took a left instead of a right to make the drive a little more scenic, adding maybe five minutes to the length of our trip. We wanted to drive past a field where my co-worker had seen three deer the week before. There were no deer, but the field was full of tall grass, with the late afternoon sunshine slanting across it, and behind, in the distance, a glimpse of the dark woods. We slowed down and took it in for a minute, then drove on.

A couple days later, we got called into the office of the human resources director, where they had a GPS map printed out, and they grilled us about it.

“I just don’t understand,” she kept saying, “why wouldn’t you take the most direct route?”

That’s right, I thought, you don’t understand, because you’ve probably never finished repairing a sewage pump, hauled the 150-pound thing back in place, then tried to wash the stink off your hands before you got in the truck.

Some people think a lot of workers are quitting their jobs these days because of the Coronavirus, because of government payments, because of the whole internet economy. I’m sure all of those are part of it, but the basic fact is that workers make less money (when adjusted for inflation), work more hours, and are much more surveilled and disciplined than we were a few decades ago. It gets tiresome, and when someone can find a way out, they’ll take it.

If you have a story to tell us about your experience with burnout and working through the pandemic, please contact us at: pineandrosesme@gmail.com