This question is often asked in frustration. Why should incarcerated people be prioritized? Some may believe that prisoners don’t have the same right to healthcare as the general public, and that whatever a prisoner did, they deserve to be incarcerated, medical neglect might even be fair punishment. Others believe prisoners deserve health care, but wonder why they were higher on the priority lists than others for a short time. These attitudes are pervasive in the criminal justice system, so it’s no wonder that when a disaster like COVID-19 happens, this attitude is voiced in public discourse.

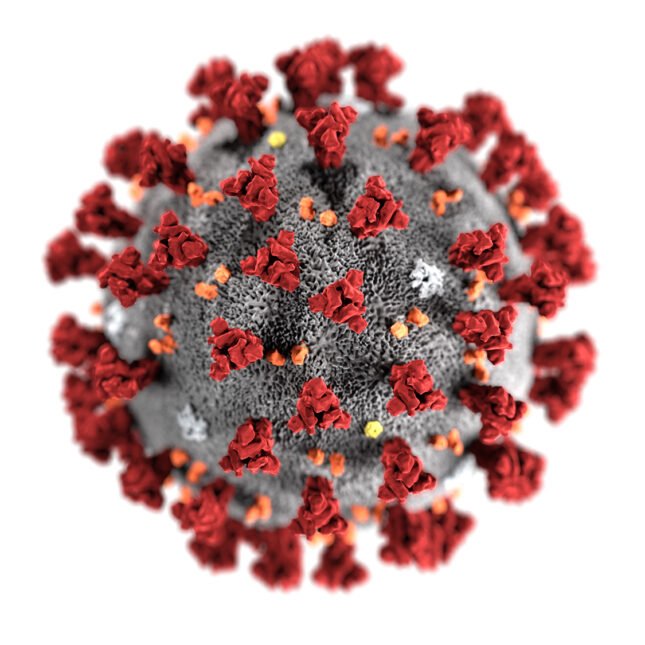

But I’ll bite and tell you why, straight from the horse’s mouth. The federal CDC acknowledges that “outbreaks in correctional and detention facilities are often difficult to control given the inability to physically distance, limited space for isolation or quarantine, and limited testing and personal protective equipment resources. Incarcerated or detained persons… may also be older or have high-risk medical conditions that place them at higher risk of experiencing severe COVID-19.” Put simply, “it may be hard to stay at least 6 feet away from other people. There may not be enough space to keep people with COVID-19 away from others. You may be sharing space with someone who has the virus and does not know it. Staff or visitors may have the virus and not know it.”

When I initially heard people question why prisoners received vaccinations before the general public, vaccine shipments into the state were sparse compared to demand, hospital vaccine hotlines were bogged down with anxious callers, and an entire population was itching to return to a time where it could congregate freely and ditch the masks. Often, this question was a rhetorical, a frustrated reaction to the poor organization of government agencies and vaccine distributors. People demanded a return to the freedom we once had.

Complicating this question was a common sense of commiseration with the incarcerated by many people to whom at-home isolation felt like “being in prison.” And especially for those already homebound, whether they be elderly, disabled, or fearful of getting sick–some without family members or home care workers to interact with–has been even more intense. The toll that isolation takes on a person is nothing to minimize.

However, there is a significant difference between the isolation that non-incarcerated people feel and that which incarcerated people experience. For one, those in their own domicile, outside of institutional settings, have far more control over their environment. You can sanitize your surroundings a la Howard Hughes Jr., you can set boundaries with others, hell, you can even board yourself up in your basement with a palette of canned beans and watch the world burn on your smartphone. You can grill your visitors about where they’ve been and if they’ve been tested, request that they wash their hands and put on masks before entering your space, and impose strict boundaries with those who don’t think COVID-19 “is that big of a deal.”

When you are a prisoner, you don’t have this kind of control. Some people in the general public are under the assumption that being a prisoner is easy because you don’t have to make decisions for yourself. But it’s not that you “don’t have to,” it’s that you can’t. There is no freedom to make decisions for your personal safety. Your cellmate may be unwilling or unable to mindfully distance from you. Your cell is cramped. Furthermore, without any mandate for prison guards to get vaccinated, and structural tendency towards neglect and cruelty in which guards operate, would you, as a prisoner, have any faith in a guard’s consideration for your safety? The anxiety that a non-incarcerated person feels during isolation is shared with those incarcerated, but people stuck in prisons also experience the endless array of issues that come with abuse, neglect, disregard and contempt from both the people in control of their environments and the people they are stuck with. The question implies that in the midst of the pandemic, prisoners were somehow receiving special treatment from state agencies. This is far from the truth.

According to “Hidden Figures: Rating the COVID Data Transparency of Prisons, Jails, and Juvenile Agencies,” published by Michele Deitch and William Bucknall of the LBJ School of Public Affairs, Maine (and the majority of US states) responded so poorly to tracking and reporting COVID-19 data in prisons and jails that they received near failing grades (of D- and F, respectively). What were the reasons for such a poor grade? Writer Evan Popp of the Maine Beacon, who tackled the subject earlier this month, outlined Maine’s issues in reporting data as an overall lack of transparency. The Maine Department of Corrections does have a weekly updated dashboard, but only shows tests, positive cases, population, and demographic data of either Male or Female. The MDOC dashboard does not show who has recovered, who has died, or how spread may have occurred, although a study by the Marshall Project provides a state-by-state breakdown. The federal CDC’s dashboard for correctional facility data reflects how incomplete data reporting is. The lack of transparency indicates, at the very least, mismanagement of COVID-19 data tracking, and at worst, a gross disregard for the health of incarcerated people and potential suppression of information that could indicate neglect and abuse. In addition to the lack of transparency from the MDOC, those people in “congregate settings” that were eligible for the vaccine earlier this year originally did not include incarcerated people themselves. That is, prison guards were prioritized over the prisoners, and prison guards were under no legal obligation to get vaccines in the first place.

So the question “why did prisoners get the vaccine before me?” turns out to shine a spotlight on the institutional contempt and popular prejudices generated by our criminal justice system. Asked another way, “Why did the person crammed in a cage with an open toilet, surrounded by abusive-by-design guards, cut off from the outside world, lacking the freedom to control their external environment, and not entitled to a well-ventilated or open space, get vaccinated before people stuck in their private homes?” Let’s take a guess. The facts speak for themselves.