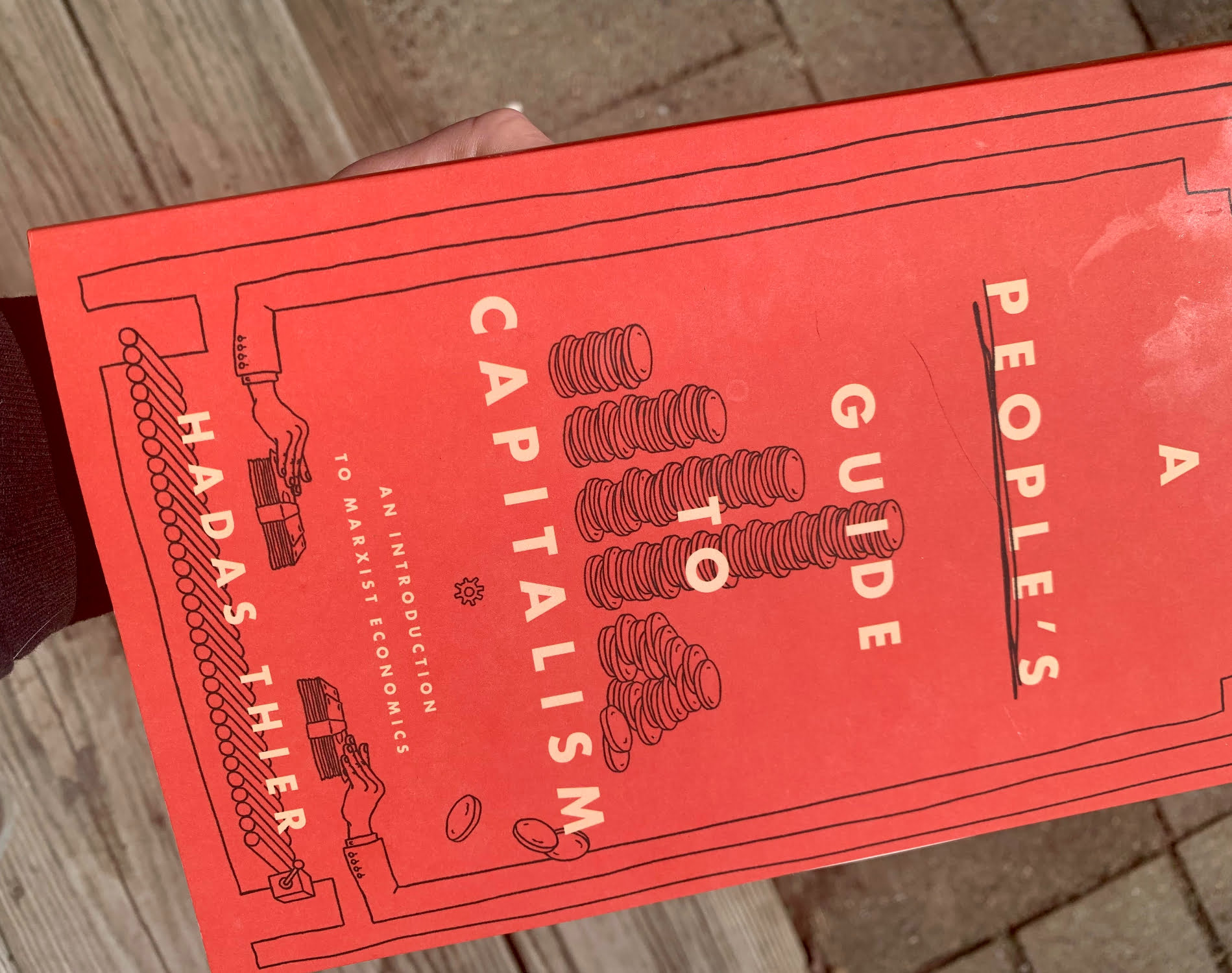

Under capitalism, our social lives are structured by an architecture of separation; private property walls us off from one another. In particular, the structural foundations of capitalism rest on an intersection of two separations.

First, those who work are separated from land, tools, and other resources they need to be able to work. Most of us live without owning things necessary to assure our survival. This is bizarre. “Digestion,” Marx writes, “requires something more than a good stomach.” Creatures in nature that have lost access to the things they need to survive, don’t. Yet we assume the separation of workers from the means of production is normal. But “nature doesn’t produce on the one hand owners of money or commodities, and on the other hand men possessing nothing but their own labor power.”

A second separation goes to how we produce and then market things. The product of labor takes the form of a commodity when it is produced independently as part of the social division of labor for market exchange. You produce one thing – maybe only your own ability to work — in order to buy all other things you need to survive. The market gathers commodities produced independently by persons or businesses isolated from one another.

The mystery of the market is where profit comes from. In principle everything is supposed to exchange for money or other commodities equal to what the thing bought or sold is worth. If the value of a chair is $100, it will exchange for a $100 bill. But if every exchange is an exchange of equivalent values, then profit can’t come from exchange. Instinctively we know profit must come from people working. Yet somehow simple understanding has become complicated and obscure.

But it’s not. Marx explains that the value of a thing depends on the amount of labor expended in producing it. Diamonds are valuable because they are rare and it takes a good bit of effort to find them. Similarly with a house or a car; effort expended determines value — the materials cost labor and putting them together costs labor. And because labor creates value, it turns out that workers, even propertyless as they are, still have something useful to take to market – their capacity to work. When a worker works, they create value, so the employer buys their ability to work in order to put them to work. Moreover, the capitalist can pay the full value of the wage and still profit. Here’s how:

Labor power sold as a commodity is worth the labor required to produce it, just like any other commodity. To produce the ability to work, the worker must be able to buy food, clothing, shelter, education, and the like, so it is the value of those things taken together that establishes the value of the commodity labor power.

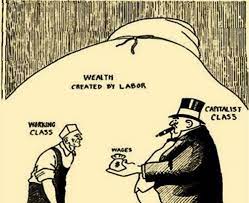

Now workers sell their capacity to labor for a day or a week, etc., and while it takes only part of that time to create the value the worker gets in a wage, labor creates value during the entire time it is employed. “No one ever makes a billion dollars,” Alexandra Ocasio-Cortez said, “you take a billion dollars.” Profit comes from the capitalist taking labor that continues after the worker has already created enough value to recover what was paid with the wage. Labor that continues beyond that point, surplus labor, is taken without any equivalent given for it. Political economy isn’t about scarcity; it’s about who controls the worker’s surplus labor.

So the mystery isn’t where profit comes from; the mystery is what drives a person to sell their capacity to labor to capital rather than producing something for themselves. The mass of humanity is propertyless because resources have been taken from them and monopolized by a few. Expropriation, theft, and dispossession throughout the globe have created propertylessness, and empty hands drive me to surrender my day’s labor — my autonomy, my life activity itself — to another in exchange for a paycheck good enough to get by, though not necessarily good enough to cover medical expenses or sick time or child care or healthy food or time off or education or unemployment or a decent retirement or dozens of other things, big and small, that go into living modestly well. Access to tools and land and raw materials can only be gained by permission of another, to whom my work and its products then belong.

And where profit drives an economy, money spawns money without limit. Socialism means the human person, not money, becomes the goal of production. We claim a vision of “labor as life’s prime need,” as the discovery and flourishing of the richness of what we are as human. But under capitalism, the purpose of production is adding money to money without end. Some adjust, find a job they like. But the system doesn’t depend on this. Most find soulless toil. Occupational disease or stress or workplace injury and overwork are just “collateral damage,” a necessary cost of investing money to make more money. And the environment is collateral damage. Moneybags takes what brings profit and treats the rest as waste, sludge, nevermind people once lived there and still do or try to. Five hundred years is not a long time in human history, but capitalism’s history, stretching back only five centuries, has brought our species to the edge of extinction.

The task for socialists, then, is to end capitalism. “For indigenous nations to live,” Glen Coulthard writes in Red Skin, White Masks, “capitalism must die.” No one is differently placed. So we can start by attacking capitalism’s structural foundations and start on this from where we are. Marx explains that the separation with which capital began must be understood as the formation of a social relation that is ongoing and needs change:

“We should find that this so-called original accumulation means nothing but a series of historical processes, resulting in a decomposition of the original union existing between the labouring Man and his Instruments of Labour. . . . The separation between the Man of Labour and the Instruments of Labour once established, such a state of things will maintain itself and reproduce itself upon a constantly increasing scale, until a new and fundamental revolution in the mode of production should again overturn it, and restore the original union in a new historical form.”

“[I]n a new historical form” — what does this mean? How do we recover the organic relationship between nature and an individual working with a tool singly adapted to them? Capital has gathered working people and developed the means of production accordingly. We’re not going back to the hand loom. But how can we recover the original union if we work now in association with one another? Loss of personal autonomy beyond the factory, farm, warehouse, or office threshold is not acceptable. To recover the original union in new historical form means taking control of the means of production together, democratically, participatively, and fully so.

For this — and with this — we’ll build a society where “the full and free development of every individual forms the ruling principle,” and where, in struggle, “from each according to ability, to each according to need” is the way we make it happen.

Howard Engelskirchen is a retired teacher of law and philosophy and the author of Capital as a Social Kind: Definitions and Transformations in the Critique of Political Economy. His activism and study of Marxism reach back decades. He is currently teaching “Capital: A Mini-Course” at Southern Maine Community College.