You may have recently heard about the Governor of Louisiana issuing a pardon to one Homer Plessy, an African American activist who dared challenge Jim Crow segregation in the 1890s in the Deep South. And you may have also read my previous article about the statue erected and still standing in Augusta, Maine dedicated to Supreme Court Chief Justice Melville W. Fuller. Fuller wrote the Supreme Court opinion in 1896 that enshrined segregation into American law by ruling against Plessy in the famous Plessy V. Ferguson. Though my article was written more than ten months ago, the more things change the more they stay the same.

By virtue of his wealth and connections, one Robert Fuller—a descendent of Chief Justice Fuller himself who paid $40,000 out of his own pocket for the statue and then “donated” it to the state—represented his own private family concerns at a public hearing last year about public property, that is, the statue’s placement on the grounds of the Kennebec County Courthouse. During the original committee hearings in Augusta about what to do with the statue, we heard Leah Baldacci (while representing the same Robert Fuller) offer up a preview of the kind of hysteria roiling around Critical Race Theory. And we got to hear another lawyer (also representing Mr. Fuller) play some of the greatest hits usually reserved for opposing the removal of Confederate monuments in the South. First among these tropes was the statue’s supposed ability to serve as a “teachable moment.” The urge to “celebrate our own hometown successes” followed close behind. After all, Chief Justice Fuller was born in Augusta and graduated from Bowdoin College. A real Mainer.

Stature of Chief Justice Melville Fuller in front of Kennebec County Courthouse. Photo credit Joe Phelan. Courtesy of Kennebec Journal file

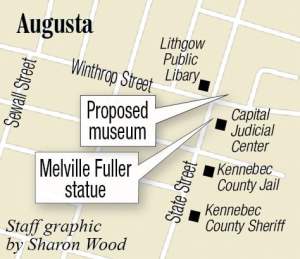

The hearings and protests surrounding the statue made the news, but many people are unaware of the committee’s final decision to remove the statue and the rationale behind it. Nor do they know much about where the statue was to be taken or about the Fuller family’s continued maneuvering to keep it in the public eye. Well, it turns out there was a reason for all this which I’ll now try to explain. It turns out—wait for it— that Robert Fuller was hatching an offensive and blatantly disrespectful plan aimed at creating a personal museum for this hate monument… right across the street from the Kennebec Courthouse!

See Mr. Robert Fuller—Chief Justice Melville W. Fuller’s descendent—was at first adamant that this statue not be moved, it should stay right where it was. Then, suddenly, he was open to the idea of simply reclaiming the statue himself and finding a private place to display it. What could have changed his mind in such a short time?

Well, this is likely due to the fact that there were serious talks going on about moving the monument to the Maine State Museum where it would be included in a new wing dedicated to Black History that would, among other things, contextualize the impact that Chief Justice Fuller had had on Black people across the country for over one hundred years. One member of the committee appointed by the Kennebec County Commissioners to decide what to do with the statues stated this explicitly in an email to the author of this article, writing, “Several of my friends have suggested throwing it in the Kennebec River… I see the situation differently. Imagine if Fuller is but a sideshow in a civil rights [display]… in the Maine Museum.”

Sometime after those discussions, Robert Fuller reversed himself, backing away from his purported desire for the statue to be used as a “teachable moment.” When given the opportunity to do just that in a profound and meaningful way by placing the statue in the civil rights display arose, Mr. Fuller decided that he wasn’t so interested in people learning about the history surrounding his ancestor.

Except now he suddenly is interested in teachable moments again. White Supremacy is a helluva drug. After almost a year of silence, Robert Fuller has decided that this monument to segregation and legal apartheid needs its own dedicated viewing space. As CentralMaine.com reports,

“Documents on file with the city’s planning bureau offer details of the Maine Judicial Heritage Society Memorial Museum at the former site of the Augusta YMCA, across the street from where the statue now sits outside the Kennebec County Courthouse at 95 State St.”

Image courtesy of CentralMaine.com

“The site plan indicates the 1.06-acre lot, which Robert Fuller Jr. bought in April 2021, would become home to a statue, a 600-square-foot maintenance building, an educational area and a small parking lot.”

It’s almost as if it was never about teaching history and this entire issue was really about erecting a monument to someone with a legacy deeply connected to oppression in the heart of Maine’s capital city. A place where people facing what is undoubtedly a broken criminal justice system would have to see it on a regular basis as part of a multi-generational attempt to whitewash the image and legacy of Chief Justice Fuller.

Now you might ask if this is all just speculation on my part. If only we had some sort of written record by Mr. Rober Fuller himself which supported the explanation I have offered here. It would be even better if Fuller’s remarks appeared in the press. Ask and you shall receive.

On September 18, 2020, the Kennebec Journal quoted a letter Fuller wrote to organizers protesting his relative’s statue. The letter decries the “defacement” of the statue by “impertinent juvenile” anti-racist activists and invokes Ghandi, Mandela, and King in condeming them. In contrast, “three generations” of Fuller’s family have “endeavored to remove this blot on the family escutcheon”—a five dollar word for family shield. And it turns out that the best way to erase the “blot” was to commission a $40,000 statue. Fuller concludes his letter by claiming that the statue was not meant to “perpetuate Plessy” but rather to “create what is today called a ‘teachable moment’ inviting the public (the judiciary included) to form an opinion not inflamed by momentary passions but maturely arrived at based on the entire record of my ancestor rather than on one opinion alone.”

The letter speaks for itself. Fuller claims Gandhi, Mandela, and King for himself and suggests that the millions in the streets for Black Lives Matter are guided by mere “momentary passions.”

“Momentary passions” on display in August. Image courtesy of CentralMaine.com

The simple fact of the matter is that this statue is unwanted. It’s unwanted because nobody wants to be associated with the person who helped codify segregation. It was unwanted by the judiciary. It was unwanted by the people of Augusta and Kennebec County.

But even after all of that, instead of chalking this up as a loss, Mr Fuller cannot help himself. He seems to be operating under the assumption that this was an erroneous outcome and that everyone who is not Robert G. Fuller, Jr. is simply an obstacle that must be overcome with even more money, social capital, and bureaucratic maneuvering. Opposition to his actions even includes members of his own family who also oppose the public veneration of a segregationist.

For me, Mr. Fuller’s actions have become disrespectful because he seems to believe that nobody will call him out. That everyone would just forget about it. Or that everyone not named Robert G. Fuller Jr. is too oblivious to put two and two together and tell him to take a hike.

I would say that the appropriate response by the Augusta Planning Board would be to tell Mr. Fuller to accept the original offer of an appropriate space for the statue presented to him a year ago in the Maine Museum civil rights exhibit and to reject the building of a shrine for his hate monument without further consideration. I would also say that a year is long enough to wait for Mr. Fuller to make arrangements. A final notice should be issued explaining to him that he is to reclaim his statue or the County will dispose of it at cost to him, since he was the one who accepted responsibility for moving it in the first place.

I like teaching accurate history that does not seek to sweep the impact of horrific legal decisions under the rug, unlike others who only pay lip service to such education for political and PR purposes. If you feel the same way you can write to the August Planning Board or show up to the meeting on February 8 at 7PM and let them know in person. And if you can’t make it in person but still want to participate you can ask that the Planning Board hold this meeting with a virtual option so that it is both recorded and accessible.