At the end of Maine’s 131st Legislative Session in June, Gov. Janet Mills signed LD1435: An Act to Reduce Commercial Sexual Exploitation into law, making Maine the first state in the country to implement what bill sponsor Rep. Lois Galgay Reckitt referred to as the “partial decriminalization” of sex work. The bill is nearly identical to one vetoed by Mills in 2021, repealing the criminalization of engaging in sex work while maintaining penalties for buyers. While humanitarian in appearance, many sex workers and advocates warn of the dangers of what’s been dubbed the “End Demand,” “Nordic,” or “Equality Model” – that “partial” decriminalization necessitates “partial” criminalization (of clients, third parties, and consequently, sex workers themselves). This style of legislation was first introduced in Sweden in 1999 with the aim of stopping sexual exploitation by ending demand – as the argument goes, “No Buyers – No Business.” Despite the End Demand model’s promises, sex workers living and working under its purview continue to experience violence, reporting increased surveillance, evictions and deportations, and negative impacts on physical, mental, and sexual health. As data from End Demand model countries show, intensified criminal penalties for purchasing sex does not necessarily decrease the buying or selling of sex, but rather, decreases its visibility in outdoor or street-based contexts. Frequently cited by End Demand proponents, the Swedish Institute’s 2010 Skarhed Report declares street-based prostitution decreased by half from 1999 to 2008, though it finds a spike in Internet-based ads and acknowledges that there is insufficient evidence to determine the number of indoor sex workers, or those working in spaces hidden from public

view.

While many pro-End Demand organizations claim it effectively mitigates trafficking, studies in Sweden have found trafficking conviction rates cut nearly in half, while reported cases rise. Melissa Sontag Broudo of Brooklyn’s SOAR Institute explained before Maine’s legislative committee that “criminalizing the purchase of sex misdirects law enforcement resources towards consensual interactions, further limiting resources available to address exploitation and trafficking.” The same Swedish study found the number of trafficking tips increased by 450% in a ten year period. In 2021, Maine’s Department of Public Safety reported two sex trafficking convictions – an important distinction from identified cases or unsubstantiated tips, as only a fraction of these will prove legitimate enough to ever see the courtroom. Inflated case and tip numbers may reflect a higher level of surveillance, but do not necessarily equate to safety. As Maine’s Deputy Police Chief Brian P. Scott attests to, “unprecedented low levels of staffing” are already spreading policing capacities thin – investigating skyrocketing numbers of unverified reports reallocates resources away from those actually experiencing exploitation.

For sex workers, increased surveillance rarely means safety. A statement by Amnesty International outlines the harm done by the End Demand model in Sweden and Norway. According to their research, heavier policing of clients creates an environment in which sex workers may have to compromise important safety strategies, like the screening of clients, use of condoms, or location – all while drawing from a smaller, competitive pool of clients who are willing to engage in higher-risk behavior. And while sex workers may no longer face criminalization for selling or trading services, they may still be prosecuted for related “quality of life” crimes – offenses like loitering, disorderly conduct, or drunkenness that are considered to decrease the feeling of safety in communities. While LD#1435 includes a provision protecting sex workers from being charged with trafficking themselves, transporting other workers or working in the same home as others does qualify as sex trafficking in Maine – meaning a “safety in numbers” strategy assumes the risk of being charged with a Class D crime (punishable by up to 364 days incarceration and a $2,000 fine). Leasing a property where sexual services are traded also counts as trafficking, putting sex workers at risk of being evicted by landlords avoiding prosecution.

In Maine, purchasing (or agreeing, or offering to purchase) sexual services is a Class E crime for first time offenders, punishable by up to six months incarceration and a $1,000 fine. However, subsequent offenses within a 2 year period are considered Class D crimes. The penalty for “commercial sexual exploitation of a minor or person with a mental disability” is a Class C crime (punishable by up to 5 years incarceration and a $5,000 fine); it’s worth noting that the Maine Human Rights Act’s definition of mental disability includes alcoholism, but excludes other substance use disorders, unless an individual has or is actively participating in a rehabilitation program. “Current use exception” laws like these have received pushback from proponents of harm reduction practices, as they deny people with “current” substance use disorders access to legal protections and reinforce surrounding stigmas.

Walter McKee of the Maine Association of Criminal Defense Lawyers opposed LD#1435 during public testimony, underlining that “there is no evidence that has been developed to determine the impact of the changes to prostitution-related crimes to date.” The bill’s Fiscal Note suggests that this reform may incur additional incarceration costs of nearly $221,000 per convicted individual if given a maximum sentence. The Maine Department of Corrections is largely funded by the State General Fund – a predominantly taxpayer generated revenue.

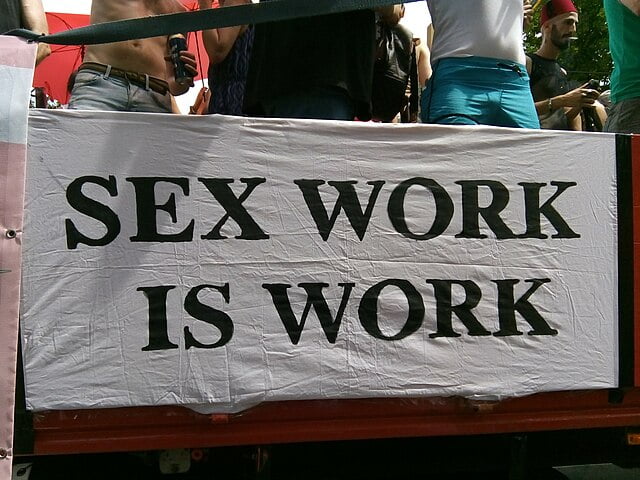

Opposition to LD#1435 was led by Mainers, with nearly 41% of public testimony from Maine residents objecting to its language or provisions. Most of these objections were in response to the bill’s conflation of exploitation with consensual sex work – as can be seen in its initial proposition to change all language of “engaging a prostitute” to “commercial sexual exploitation” throughout the Maine Criminal Code. This amendment was struck from the final draft (except in instances referring to minors or individuals with a mental disability), yet responses from the bill’s supporters point to the perseverance of its underlying ideology. “When acknowledged, as the victims they are, and supported, these people will be well on their way to becoming contributing members of society with a renewed sense of self-worth and enterprise,” said Rep. Lynn Copeland of Saco, co-sponsor of LD#1435. The forced victimization of sex workers that is found in nearly every public testimony supportive of the bill faced backlash from local and national advocates: “What it fails to acknowledge is that there are also adults capable of making informed decisions about their own bodies and livelihoods, who are neither criminals nor victims. All these people are equally deserving of safety and dignity,” said Destie Sprague of Maine Women’s Lobby. “It also likens consenting adults to people who legally cannot consent, which is problematic on its own but is also a slippery slope to future limitations of bodily autonomy,” adds Sontag Broudo, drawing a parallel to recent attacks on reproductive rights.

Lois Galgay Reckitt explained her inspiration for drafting a bill aiming to “end this system of inherit exploitation” and the “devaluing of all women in society” came from a Portland patrol officer who wanted to make an “impact” on street-based sex work. From LD#1435’s conception, it has been led by legislators and police, rather than the people it claims to protect. Those with previous experience selling or trading sex in Maine made up 0.1% of testimony. No public comment was heard from currently active sex workers. LD#1435’s provisions are rooted in a “rescue industry” which gives little opportunity for sex workers to exercise agency over their own lives, and refuses to listen when they do.

If you’d like to learn more about the realities of the End Demand model, check out these resources: